You may be thinking, what the heck is a monoid, and why the heck is it vertical? To explain this we will need some insight into classical categories and $2$-categories, which we luckily have been developing for the last few posts. First off, to let the familiar readers know, the objects of study today is called monads, not vertical monoids. But, I like to visualize them and think about them as somehow vertical, or at least something not strictly horizontal or one-dimensional.

Not everyone is familiar with monoids, so to set the stage for the rest of the post we define a monoid to be a set $M$ together with a map $\mu:M\times M\longrightarrow M$ and a distinguished element $1 \in M$ such that $m(a, 1) = a = m(1, a)$ and $m(m(a, b), c) = m(a, m(b, c))$ for all $a, b, c \in M$. This makes m an associative multiplication on $M$ with a two-sided unit $1$. We can kind of think about a monoid as a group without inverses, but pulling all intuition from groups might turn out bad.

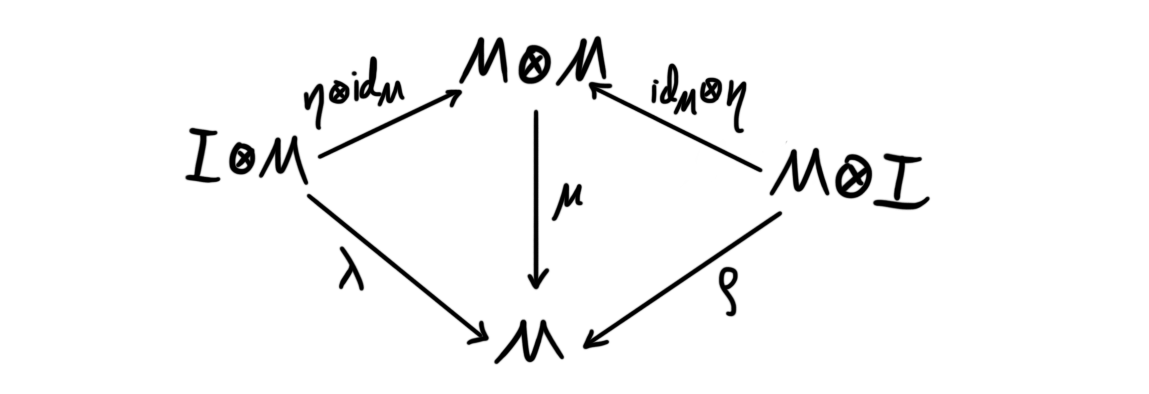

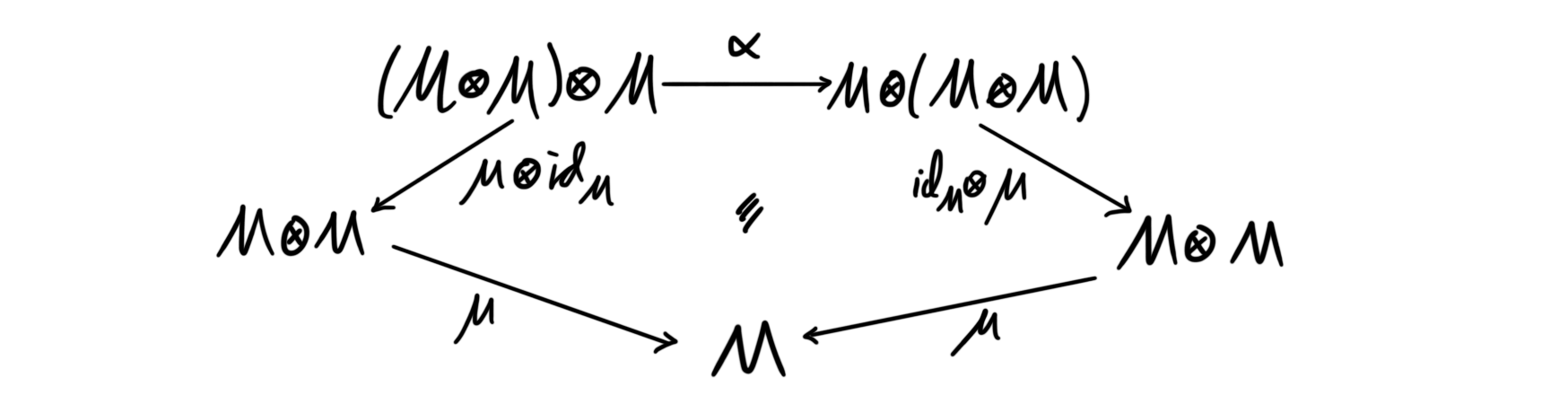

We can define more general versions of monoids by using category theory. This makes use of monoidal categories, which we have talked about a little while ago. A monoid in a monoidal category $(\mathcal{C}, \otimes, I)$ is an object $M$ together with a map $\mu:M\otimes M\longrightarrow M$, called multiplication, and a map $\eta: I\longrightarrow M$, called the unit, such that the associative law and left and right unit laws hold.

Here $\alpha$ is the associator in the monoidal category and $\lambda$, $\rho$ are the unitors. These are described a bit in the previously mentioned post. We see that this notion of monoid in a monoidal category is essentially equal to the one previously stated using sets, in fact the first definition is the same as a monoid in the monoidal category of sets, $Set$.

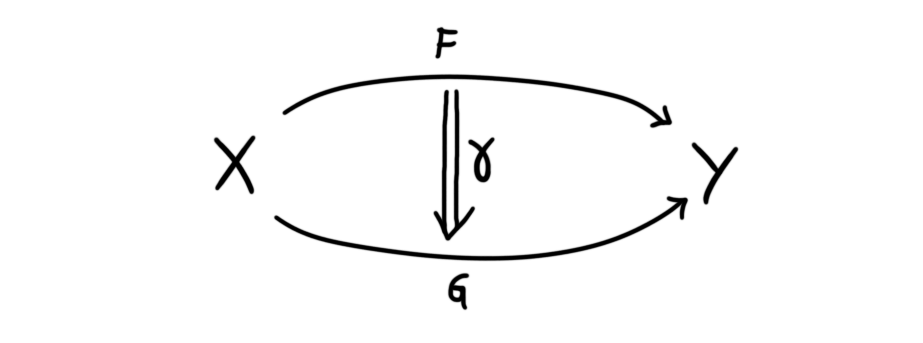

If we recall back to the discussion about $2$-categories in the earlier post about the homotopy hypothesis, we defined what we called vertical composition of $2$-morphisms. This notion of vertical is the reason for saying that monads are somehow vertical monoids. If we draw $1$-morphisms horizontally, as we usually do, then we can draw $2$-morphisms vertically.

Which makes this whole notion of vertical composition a bit more graphical. In a $2$-category $\mathcal{C}$ we always have a category $B(X, Y)$ of morphisms between objects. If we restrict ourselves to $1$-endomorphisms we can define a monoid in the monoidal category $B(X, X)$. Here the monoidal structure comes from composition of $1$-endomorphisms. If we recall what we need in order to have a monoidal category, we need a product (which here is horizonal composition), a unit (which here is the identity $1$-morphism $id_X$ at an object $X$), an associator and two unitors, that respectively satisfy the pentagon identity and the triangle identity. This is already ingrained into the definition of a $2$-category, and is made very explicit in the model we presented, i.e. bicategories. A monoid in this monoidal category of $1$-endomorphisms is the definition of a monad in a $2$-category. To make this even more explicit, and to summarize a kind of wild paragraph, we present a rigorous definition.

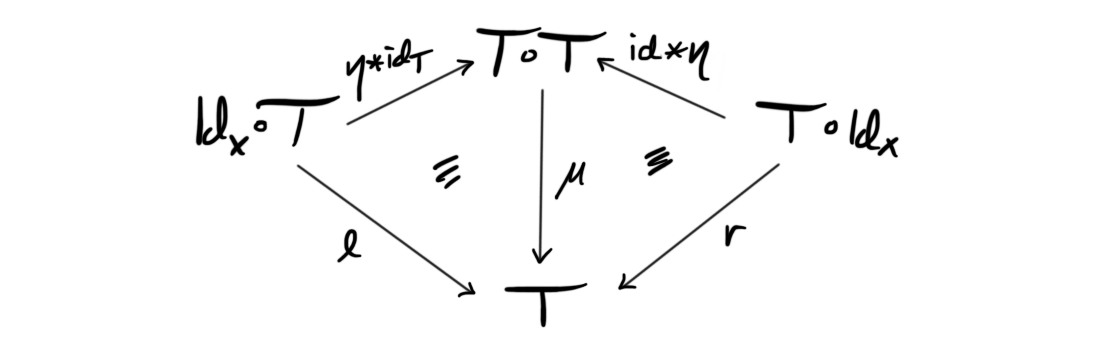

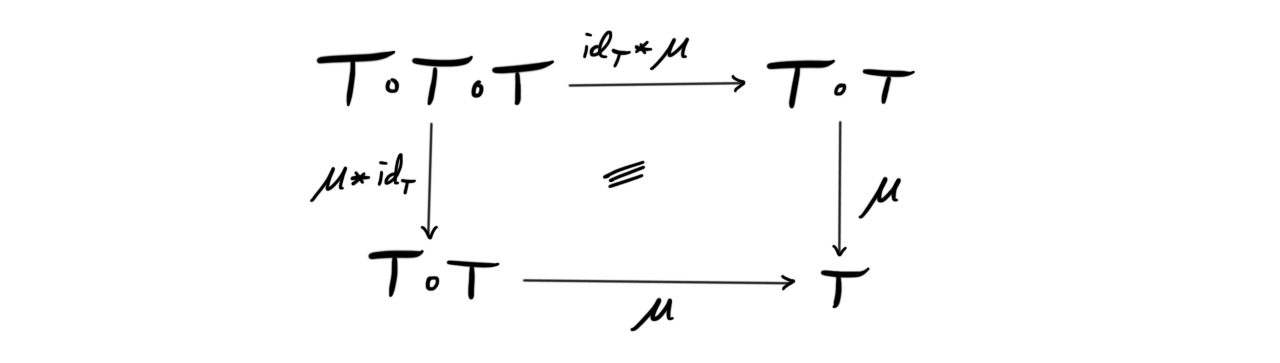

Definition (Monad): A monad $(X, T, \mu, \eta)$ consists of an object $X$, a $1$-endomorphism $T$, i.e. an object in the category of endomorphisms $B(X, X)$ together with two $2$-morphisms $\mu: T\circ T\longrightarrow T$ and $\eta: Id_X\longrightarrow T$, such that the diagrams

and

commute.

In the more classical setting, the definition of a monad comes from endofunctors of categories, i.e. $1$-endomorphisms in the category of categories, $Cat$. The most important, or at least some important examples of such monads comes from adjunctions. In fact every adjunction pair $(F, G)$ defines a monad. Here $G\circ F$ defines an endofunctor $T=G\circ F: \mathcal{C}\longrightarrow \mathcal{C}$, the adjunction unit is a natural transformation $\eta: Id_{\mathcal{C}}\longrightarrow G\circ F$ and the monad multiplication comes from the adjunction counit $\epsilon$ by

$$\mu: T\circ T = G\circ F\circ G\circ F \overset{id_G \circ \epsilon \circ id_F}\longrightarrow G\circ F = T$$

This monad kind of measures the failure of the adjoint pair $(F, G)$ to be an equivalence of categories.

The classical definition of a monoid i.e. the one using just sets can also be reformulated in this setting by letting our $2$-category have only one object, letting $1$-morphisms be sets where composition of sets is the cartesian product, and the $2$-morphisms be morphisms of sets. A monad in this category is then just a monoid. This idea is from John Baez, who also talks about connections to Feynman diagrams in physics in his posts. I don’t know enough physics to explore this now, but maybe another time.