Last fall I held a talk about functors, natural transformations and equivalences of categories. This talk was part two of five in a student seminar on introductory category theory. There was mostly second year students attending but also a couple more experienced students. To make the talk a bit interesting for them as well I said that an equivalence of categories is the correct notion of “sameness” of categories, and not isomorphisms due to the fact that categories naturally lie in a $2$-category. An isomorphism of categories would be the correct notion of sameness if the category of categories had only trivial $2$-categorical structure, and we didn’t have to worry about higher morphisms. In this post I want to look at this statement and show that it is true.

Motivation and hand waving

Last post we talked a bit about $2$-categories and the differences between strict and weak $2$-categories. We introduced these through $Cat$, the category of (small) categories, which we discovered was a strict $2$-category. We also defined a bicategory, which is a way to explicitly describe a weak $2$-category. It can be smart to read that post to have some familiarity with the notion of $2$-categories. Since strict $2$-categories are special cases of weak $2$-categories, I will for simply use the term $2$-category instead of explicitly referring to one of them for most of this post.

In normal category theory we have for long understood that objects are not to be classified using equality, but some weaker notion of equivalence, usually called isomorphisms. For example in the category of abelian groups we want to use the first isomorphism theorem. This says that the image of a group homomorphism $f:G\longrightarrow H$, is isomorphic to the domain modulo the kernel of the homomorphism. These two groups are essentially the same, i.e. the induced morphism on the quotient $\overline{f}:G/Ker(f)\longrightarrow Im(f)$ is an isomorphism. If we were only allowed to talk about groups being equal, this would not be a useful theorem, and our theory in general would not be as rich. So, we have learned that equality of objects is a bad notion in a standard category.

Classical theory

To understand what equivalences and isomorphisms of categories are, and how they relate to this higher $2$-categorical structure, we need to look at their classical definitions.

Definition (Isomorphism of categories): A functor $F:\mathcal{C}\longrightarrow \mathcal{D}$ is called an isomorphism of categories if there exists a functor $G:\mathcal{D}\longrightarrow \mathcal{C}$ such that $G\circ F= id_{\mathcal{C}}$ and $F\circ G = id_{\mathcal{D}}$.

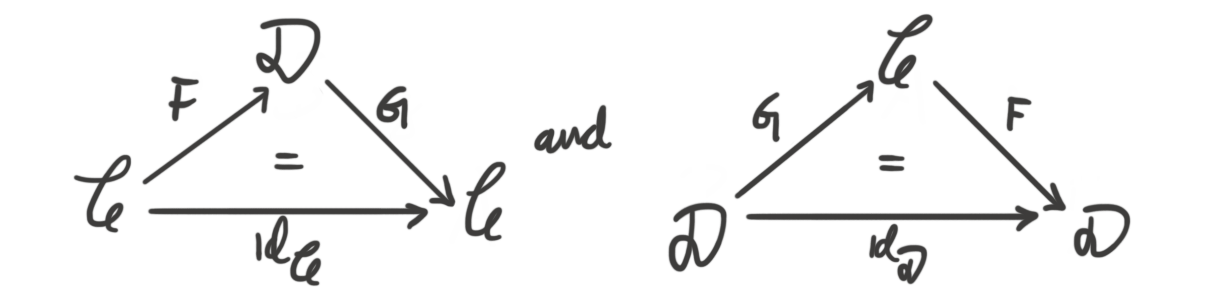

To use a very suggesting notation, we let $=$ denote that the diagram commutes. Then we can express the definition as the two following diagrams.

Note in particular that we have equalities $G\circ F = Id_{\mathcal{C}}$ and $F\circ G = Id_{\mathcal{D}}$. This is of course just because of composition, but remember that existence of composition is an axiom in the definition of a category. A priori, if we didn’t know we lived in a category, composition may not be defined. We could of course do two things in succession, but this does not a priori define a map. For example, if our objects are the points on a topological space, and the maps are paths parametrized by the unit interval, then composition of two paths is no longer a morphism, since it requires a twice as long interval. This can be fixed by a homotopy, but if we don’t pass to homotopy-classes if paths we will have undefined composition. This remark will become more important in a bit. Similarly we state the classical definition of an equivalence of categories.

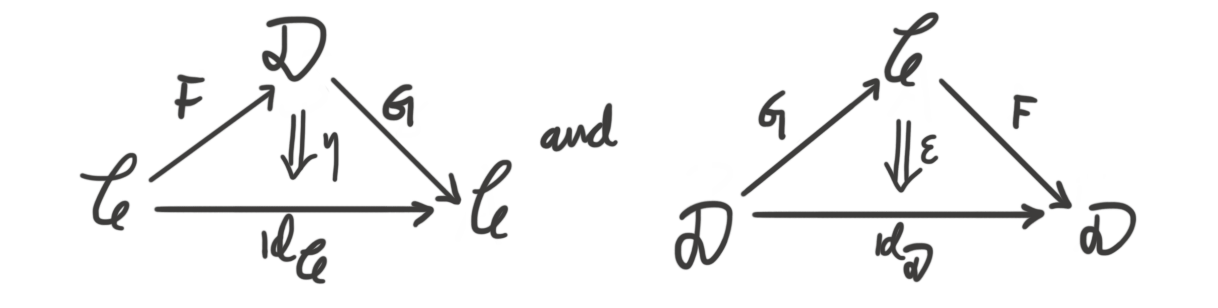

Definition (Equivalence of categories): A functor $F:\mathcal{C}\longrightarrow \mathcal{D}$ is called an equivalence of categories if there exists a functor $G:\mathcal{D}\longrightarrow \mathcal{C}$ and two natural isomorphisms $\eta$ and $\epsilon$, such that $G\circ F \overset{\eta}\implies id_{\mathcal{C}}$ and $F\circ G \overset{\epsilon}\implies id_{\mathcal{D}}$.

To again use very leading diagram drawings, we can express the definition through the following two diagrams.

If we recall back to last post, we said that the category of (small) categories, $Cat$, naturally had the structure of a strict $2$-category, but a $2$-category nevertheless. This structure came from letting the objects be the categories, the $1$-morphisms be the functors and the $2$-morphisms be the natural transformations. But, we can also have another $2$-category structure on $Cat$, namely the trivial one. Any category is trivially a strict $2$-category, just by letting all $2$-morphisms be trivial, i.e. equalities. This is of course strict since composition of $1$-morphisms, i.e. normal morphisms in the category are associative by definition. Now we are starting to form the full picture of the statement, namely that the difference between equivalences of categories and isomorphisms is the choice of the canonical or the trivial $2$-category structure on $Cat$.

Equivalences in 2-categories

The last piece of the puzzle is the following discussion. In a general $2$-category, say described by a bicategory, we have objects, i.e. $0$-cells, and categories of morphisms between them. Thus, as we have learned in the hand waving part, it is bad to talk about equality between the $1$-cells in a bicategory, as they themselves are objects in a category. So what would we then want to describe very similar $1$-cells? Since the $1$-cells and $2$-cells are respectively objects and morphisms in a category, we have the notion of a $2$-cell being an isomorphism. This means that it is invertible on the nose. Since $2$-cells aren’t the objects in some category, we can easily talk about equality between them, and invertible then means that we have an actual inverse. Hence we can define very similar $2$-cells to be the $2$-cells that are invertible up to a $2$-cell isomorphism. This is called an equivalence in a $2$-category.

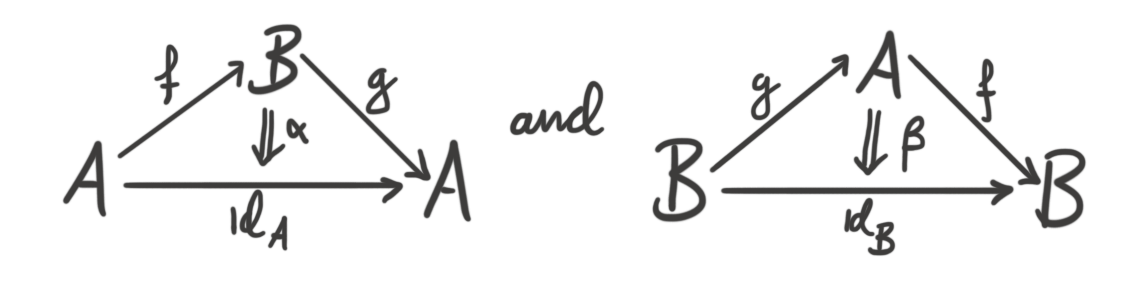

Definition (Equivalence in a 2-category): Let $A, B$ be $0$-cells in a bicategory $\mathcal{C}$. A $1$-cell in $\mathcal{C}$, i.e. an object $f:A\longrightarrow B$ in the category $\mathcal{C}(A, B)$, is called an equivalence if there exists a $1$-cell in $\mathcal{C}(B, A)$, $g:B\longrightarrow A$ and two isomorphism $2$-cells $\alpha: g\circ f\implies id_A$ and $\beta f\circ g \implies id_B$.

Maybe a “new” cool drawing makes things simpler, more intuitive and hopefully more familiar.

These diagrams mysteriously look very similar to the ones defining equivalences of categories. The diagrams also visualize a bit better why we call the different pieces $0$, $1$ and $2$-cells, as they operate in the same way n-cells do in topology, especially simplicial sets. If we let our $2$-category be $Cat$ with the trivial $2$-morphisms, we see that an equivalence in that $2$-category is nothing but an isomorphism, since the $2$-isomorphism connecting the composition and the identity is the “equality morphism”. In the canonical $2$-category structure on $Cat$ we see that an equivalence in that $2$-category is an equivalence of categories, since the composition is connected to the identity functors by a $2$-isomorphism, also called a natural isomorphism in the classical setting.

This is the full picture, and we have explained what we set out to do!