In the most recent blog post we discussed homotopy associativity and how to transfer algebraic structures on topological spaces. There we in particular used topological groups, which are topological spaces with group structures. That said, any group is a topological group by equipping it with the discrete topology. So if we want to study some actual topology, and not just glorified group theory, we need to look at where multiplications and binary operations arise naturally in topology.

The first place to start could maybe be Lie groups. These are manifolds with group structures, and are “more” topological than just all topological groups. Even though these groups are incredibly useful and have a rich theory associated to them, they are not the focus of this blog post. Actually having group structure is often too strict for situations where binary operations arise more naturally in topology, so let’s look at the bare minimum that we could have.

H-spaces

In topology we are fortunate enough to have a nice notion of homotopy. This we have discussed at length in the fibration series, which resulted in exploring some theory about model categories. In the homotopy category of topological spaces we argued that we can study homotopy classes of maps instead of inverted weak equivalences. This allows us to make some nice definitions of algebraic structures in the category of topological spaces. For example we can define a H-group to be a topological space with operations such that it is a group in the homotopy category. This allows for the operations to be invertible, associative and unital up to homotopy instead of on the nose. Here the “H” stands for Hopf, as in the mathematician Heinz Hopf, as the maybe intuitive name, homotopy group, is already occupied. We said we would look at the bare minimum, so instead of a H-group, we look at an H-space.

Definition: An H-space is a topological space $X$, together with a binary operation $m$, that has a unit up to homotopy. Alternatively, it can be described as a space with the operation m such that it is a unital magma in the homotopy category.

Some of the most famous examples are the spheres $S^0$, $S^1$, $S^3$ and $S^7$. These are H-spaces as they inherit an operation from the real division algebra they are the unit-length subset of. For example $S^3$ sits as the vectors in $\mathbb{H}$, the quaternions, with length 1, and the other ones in $\mathbb{R}$, $\mathbb{C}$ and $\mathbb{O}$ respectively. The first three are actually groups, making them Lie groups, but $\mathbb{O}$ is non-associative, and hence $S^7$ is as well, so its not a group. The interesting fact that these four spheres are the only H-spaces is related to the famous Hopf invariant one problem, solved by Frank Adams.

We said we wanted to stay away from groups, but here we are, back again.. Let’s actually see a non-group example. The most important one for us will be loop spaces.

Loop spaces

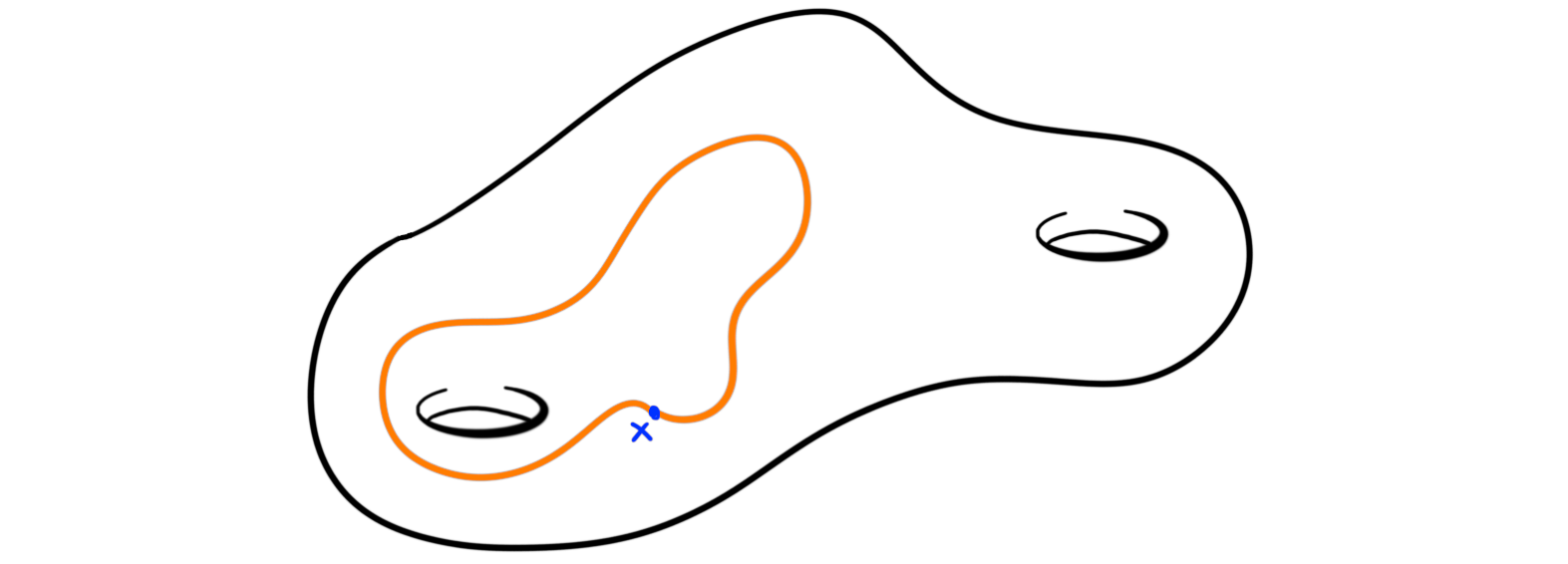

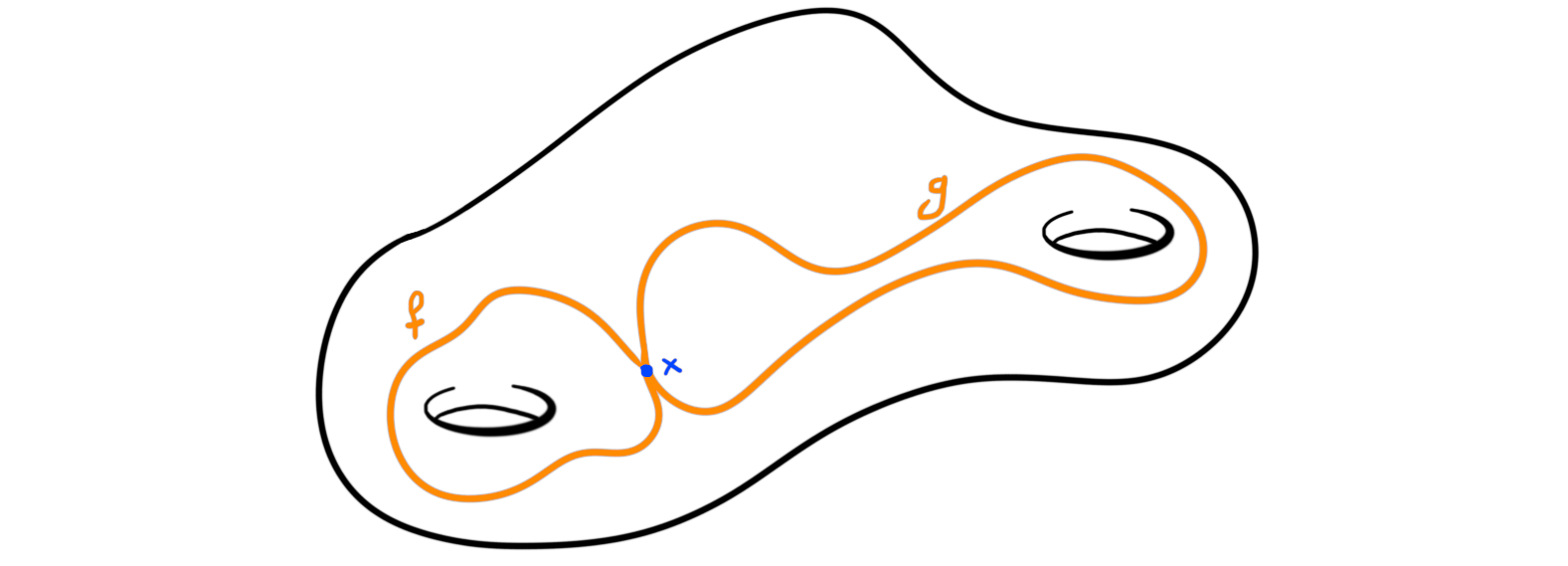

Definition: Let $(X, x)$ be a pointed topological space, abusively denoted just by $X$. The loop space of $X$, denoted $\Omega X$, is defined to be the set of continuous maps $\Omega X = \{ f\colon I\longrightarrow X \vert f(1)=x=f(0)\}$, where $I$ is the unit interval. As the endpoints of the interval gets mapped to the same point we get a loop, hence the name.

We turn this into a H-space by defining our operation to be concatenation of loops. As two elements in $\Omega X$ are two loops starting and ending at the same point $x$, we can simply join them to be a single loop that happens to pass through $x$ in the middle. More rigorously we define

$$(g\ast f) (t) = \begin{cases} f(2t), t\in [0, 1/2] \\ g(2t-1), t\in [1/2, 1] \end{cases}$$

This makes $g\ast f$ into a loop, i.e. a map from the interval to $X$ with value $x$ at the endpoints. This means that we traverse the first loop $f$ at double the speed, and then the second loop $g$ at double the speed. This is to make sure we have a map from the interval, and not from $[0, 2]$.

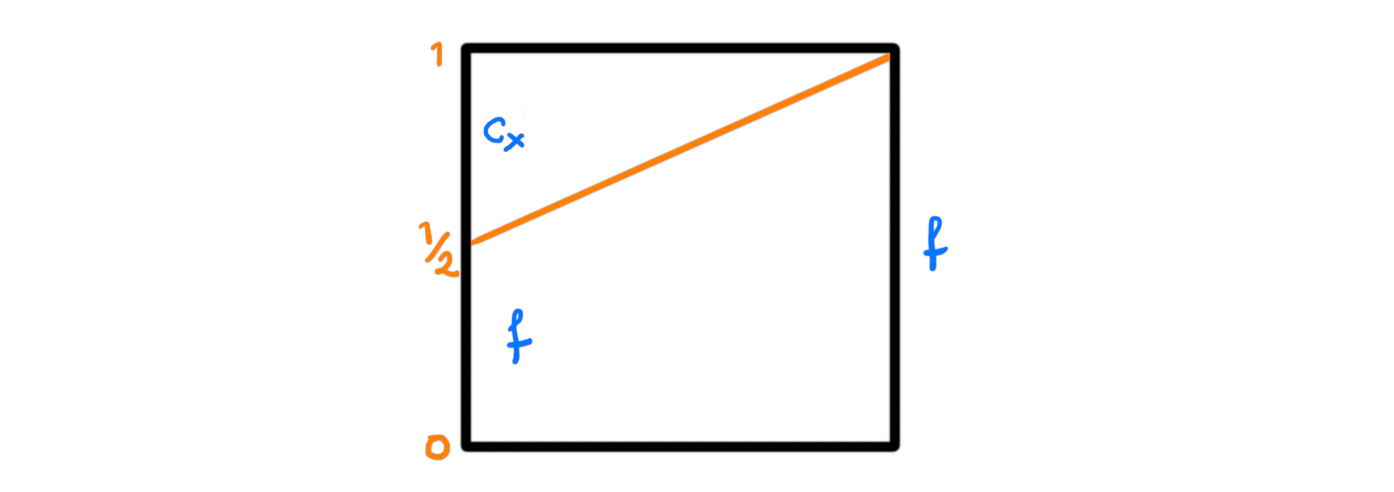

Since it is supposed to be a H-space we need a (up to homotopy) unit. This is given by the constant loop at $x$, which we denote by $c_x$. As we have

$$(c_x\ast f) (t) = \begin{cases} f(2t), t\in [0, 1/2] \\ c_x(2t-1) = x, t\in [1/2, 1] \end{cases}$$

we get a homotopy to the loop $f$ by just reparametrizing the intervals. The homotopy is a map $h\colon I\times I\longrightarrow X$ such that $h(0, t) = c_x\ast f$ and $h(1, t)=f$, and is given by $h(s, t)= (1-s)(c_x\ast f)(t) + sf(t)$, or drawn graphically by the following square:

Notice that composition of three loops $f$, $g$, $h$ can be done in two different ways. We can do $h\ast(g\ast f)$ or $(h\ast g)\ast f$. These are different because

\begin{aligned}

((h\ast g)\ast f) (t)

&=

\begin{cases}

f(2t), t\in [0, 1/2] \\

(g\ast h)(2t-1), t\in [1/2, 1]

\end{cases} \\

&=

\begin{cases}

f(2t), t\in [0, 1/2] \\

g(2\cdot(2t-1)), t\in [1/2, 3/4] \\

h(2\cdot(2t-1)-1), t\in [3/4, 1]

\end{cases} \\

&=

\begin{cases}

f(2t), t\in [0, 1/2] \\

g(4t-2), t\in [1/2, 3/4] \\

h(4t-3), t\in [3/4, 1]

\end{cases}

\end{aligned}

and

\begin{aligned}

(h\ast (g\ast f)) (t)

&=

\begin{cases}

(g\ast f)(2t), t\in [0, 1/2] \\

h(2t-1), t\in [1/2, 1]

\end{cases} \\

&=

\begin{cases}

f(2\cdot2t), t\in [0, 1/4] \\

g(2\cdot(2t-1)), t\in [1/4, 1/2] \\

h(2t-1), t\in [1/2, 1]

\end{cases} \\

&=

\begin{cases}

f(4t), t\in [0, 1/4] \\

g(4t-2), t\in [1/4, 1/2] \\

h(2t-1), t\in [1/2, 1]

\end{cases}

\end{aligned}

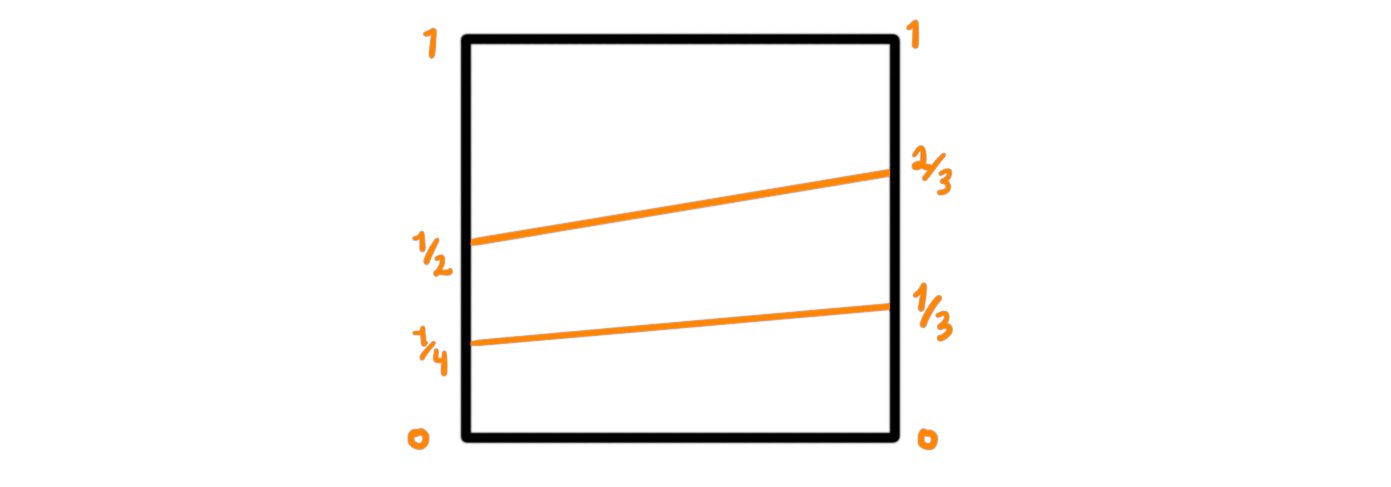

which seem similar, but are parametrized on the interval I differently. Fear not, these can also be reparametrized by a homotopy, so the concatenation of loops is associative up to homotopy! This homotopy can be drawn as follows:

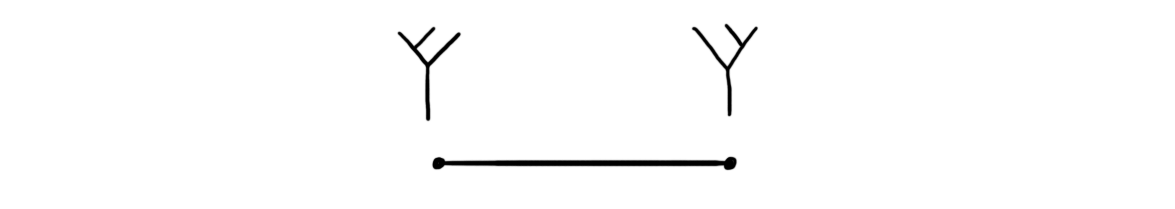

From last time we maybe remember what this means. Having a homotopy between the two ways of combining three elements with a product is the same as an action from the third Stasheff associahedra, $K3$:

By iteratively using this homotopy as well as higher dimensional reparametrization cubes on the different ways of using concatenation of loops on bigger and bigger sets of loops, we in fact get actions from all $Kn$. This means that a loop space is an example of an $A_\infty$-space, which we defined last post as a space with an action from the Stasheff operad.

In a way it is also the only example, as a space $X$ is a loop space if and only if it is an $A_\infty$-space and its monoid $\pi_0(X)$ of connected components is a a group. We still haven’t properly defined $A_\infty$-spaces and $A_\infty$ structures, and we will not do so in this post either. Not even in the next post I think. But it is coming, sometime in the future. For now, whenever someone says $A_\infty$-space, think about loop spaces, and these actions from the Stasheff associahedra.